My favorite products at local farm stands and farmers markets (besides the bounty of fresh fruit and vegetables, of course!) are the delicious baked goods and jarred concoctions crafted from the fresh ingredients, and not insignificant labor, of neighboring producers. The sweet and sticky fruit jams and jellies, the delicate and fragrant herb scones, the robust salsas and tomato sauces are unbeatable. Consumers appreciate the time and energy spent creating them, but do they fully realize the effort it took to bring those valued products to market?

A cottage is understood to be a small house, usually in the country, and the term is used charmingly in this context to represent small-scale food enterprises run in home kitchens. Certainly, passion drives the pursuit but so, too, must determination and the negotiation of assorted rules that govern the cottage food industry. However, for many, as long as the business doesn’t grow too large, or produce foods deemed high-risk, they can often escape many legal requirements that their larger commercial brethren face.

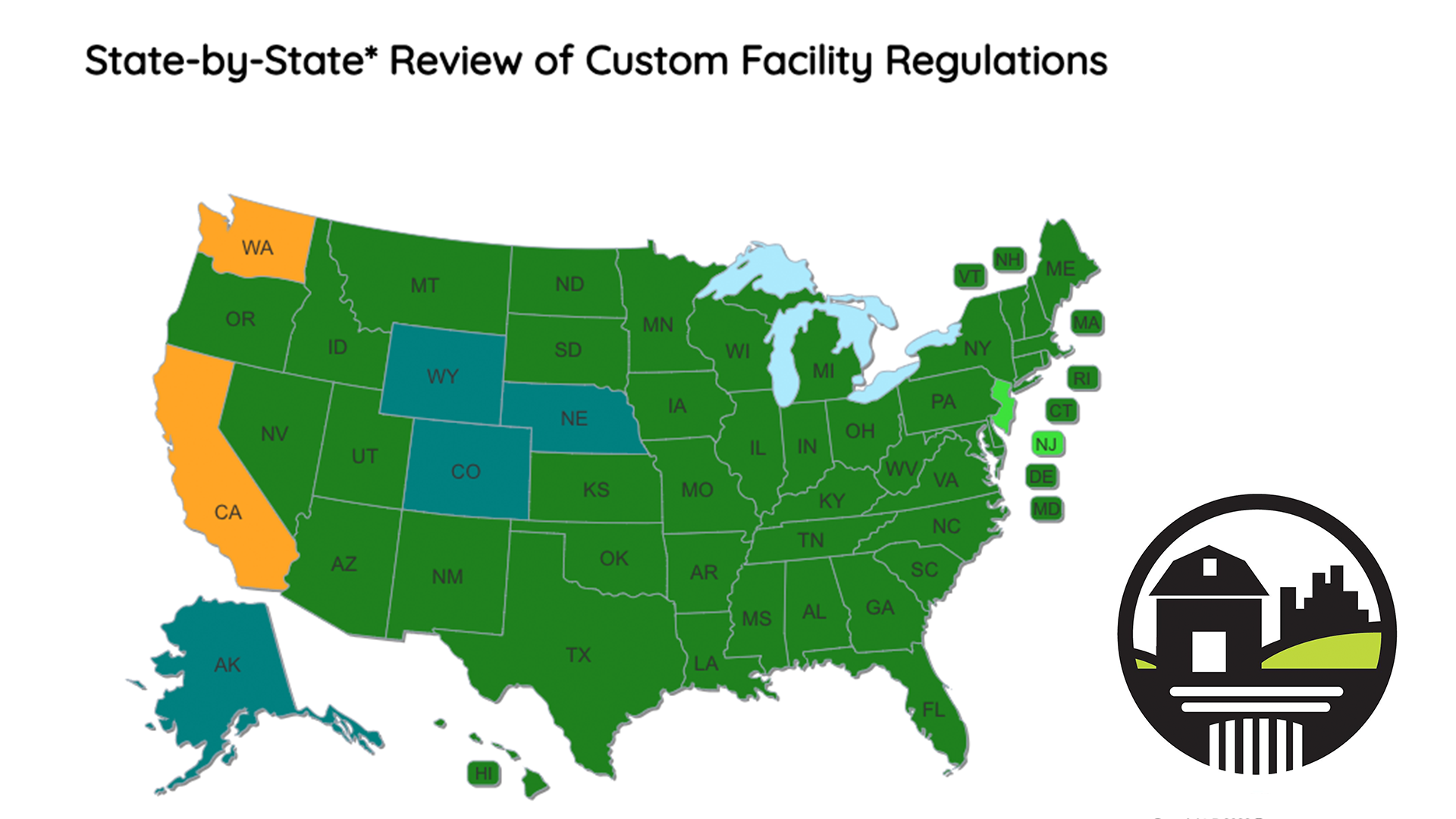

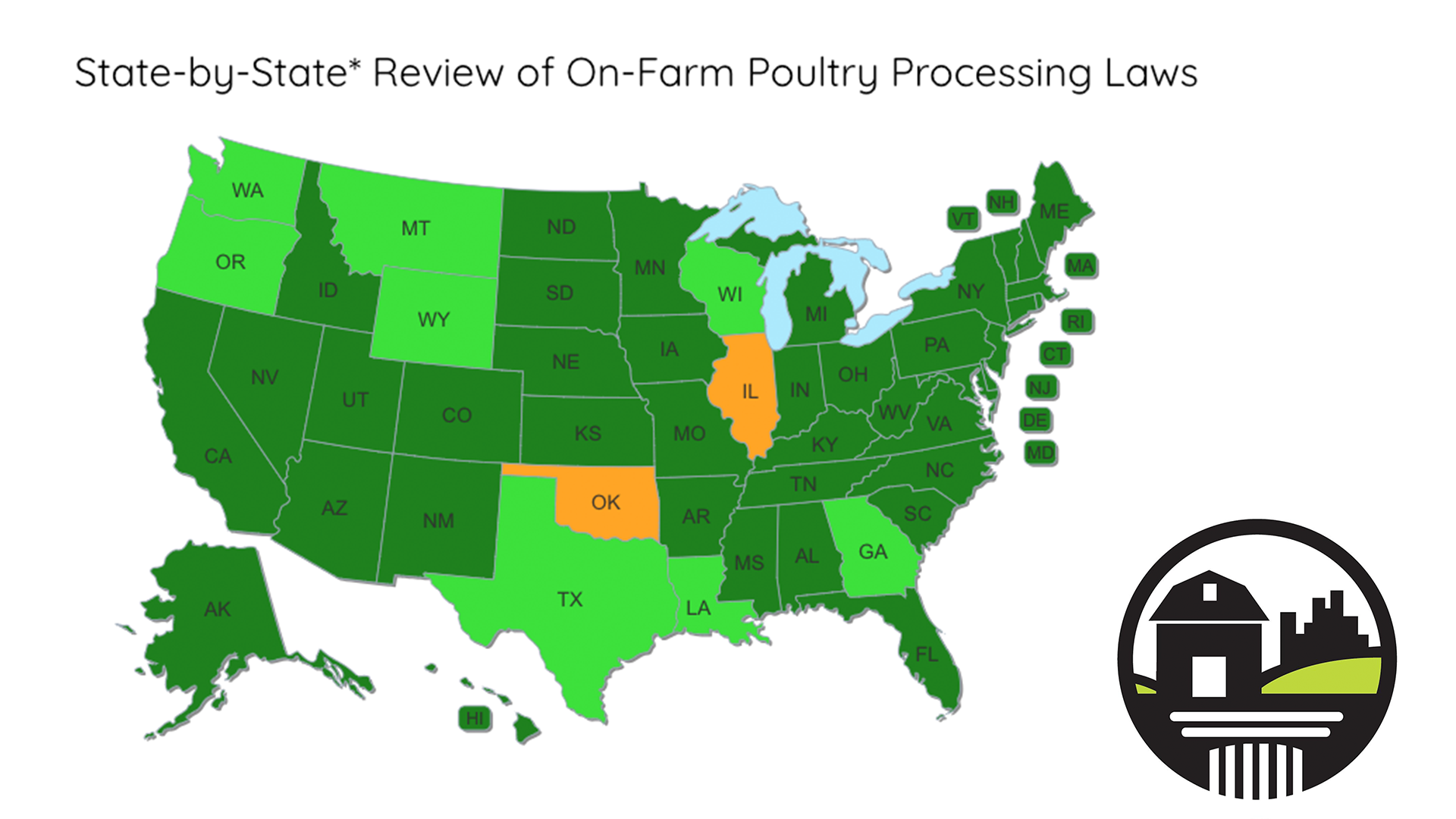

As with regulations governing raw milk production, meat processing, and similar farming activities, the laws addressing the cottage food industry vary by state, and even at the county level, with some leaning more restrictive and others being very permissive. Wyoming, for example, has a very friendly Food Freedom Act that has resulted in the elimination of most licensing, fee, and zoning approval requirements.

As a potential entrepreneur, you must do your homework and understand your state and local rules before proceeding; however, there are some general principles you can expect to confront as you prepare recipes, product lists, and business plans. We aim to cover the basics here to help prepare you for what to expect.

The Laws

The Cottage Food Map and Chart is a useful starting off point and presents a high-level overview of the various state cottage food laws around the country. In addition to citations of the laws in each state, the map and chart offer some basic details about foods that are allowed and special labelling or other requirements that must be met.

Once you have a sense of what your state allows, it’s important to get a handle on what your locality’s zoning, health, and other rules allow or prevent, and to understand in what zoning district your property lies. Although there has been a recent trend across states to prevent cities and towns from passing local ordinances that are more restrictive than those at the state level, there are still many such regulations to be considered before proceeding. You don’t want to find out too late that a cottage food business permitted by the state is blocked by your town government’s zoning regulations prohibiting food businesses in residential districts, for example. Or, that you cannot stand up your operation until you meet local requirements like safety testing your products at a lab.

While most home food businesses are too small to create the type of quality of life or nuisance (e.g. noise, smell, crowds) concerns that zoning laws often exist to mitigate, there may still be constrictions—on parking, signage, septic use, etc.—that must be negotiated. And don’t assume you’re safe if another business operates only doors down from you, as zoning regulations can differ from neighborhood to neighborhood and street to street.

Most local ordinances can easily be found and researched online. It’s a good starting point to get a handle on your position, but it’s also a good idea to contact the appropriate personnel governing the rules and confirm with them your understanding of what is permissible.

Food Products

Once you have satisfactorily cleared any local zoning and other regulatory hurdles, you can turn your attention to the fun part of your venture—deciding what food products you will make. This may largely depend on what you grow and what your vision is for repurposing those goods into products to tempt potential customers. Also, will you source some of your ingredients from other producers or retailers? If you decide to make spaghetti sauce from your abundant tomatoes, will it also include garlic bought in bulk from a restaurant supply depot? When product lists and recipes have been compiled and sourcing decisions made, it’s time to consider how the regulatory authorities, i.e. the state health department and the department of agriculture, in your area view those products and into which food safety categories they fall.

High-Risk and Low-Risk

In most cottage food laws, there are two key product groups, low and high-risk foods, and regulations can differ in how each category is defined and what foods fall into each. Low-risk foods can often, but not always, be prepared in a home kitchen without licensing, making it easier to venture into food production without having to meet difficult and potentially costly licensing and other requirements. Such products can include bread, jams, and pickles; foods that through cooking or naturally occurring properties have had harmful bacteria removed. Breads are often baked at high enough temperatures to reduce risk, and foods that are naturally acidic or have been sufficiently acidified through the addition of vinegar, for example, contain enzymes that prevent the promotion of unsafe toxins.

If your plan includes foods deemed high-risk, you will likely need a license, usually from the state health department, and you may need to build your kitchen, septic and water systems, and other aspects of the business to meet required specifications. Meat, dairy, eggs, and certain kinds of pies (think banana cream) carry an increased risk of foodborne illness because they require proper refrigeration to prevent dangerous decay. The key test is whether the food item in question is a perishable item or contains a perishable ingredient. A bread stuffed with meat, though baked, will present a problem if not stored at proper temperatures and is often deemed high-risk. Canned foods, unless they are highly acidic like pickles, are almost always problematic because improper canning practices can lead to botulism. Many states, therefore, discourage or prohibit them in home production operations.

Requirements

Even when dealing with non-potentially hazardous or low-risk foods, it’s always wise to check state requirements before opening for business. In some states, such as Ohio, a small producer making low-risk foods can generally stand up their operation as soon as they are ready to start cooking without having to register or get licensed first. Others, like Minnesota for example, ask that an operator first register with the department of agriculture and take a food safety course. States sometimes set a ceiling on the amount of sales that are allowed before licensing or other requirements kick in; Minnesota’s limit is $18,000 a year, whereas Wyoming, at the opposite end of the spectrum, has set their sales limit at $250,000.

Product testing in a lab is required in some states to ensure that a food’s pH and water activity levels are within a range deemed safe. And labeling requirements also exist in most states and typically ask that a producer include their contact operation, an ingredient list, and a statement that the food is produced in a home kitchen, among other details. A producer will want to tackle and plan for these operational needs as part of their up-front budgeting and financial assessments rather than being surprised by them down the road as the day-to-day running of the business demands most of their attention.

A producer must also understand to whom she is allowed to sell her products and where. In some locations, only direct-to-consumer sales are allowed and in others, products can also be sold at farmers markets or from farm stands, at county fairs, and the like. More lenient states even permit sales to grocery stores and restaurants.

You Can Do It!

None of this should stop our members from fulfilling their own food producing dreams. Yes, there are a variety of considerations and regulations to consider, but they are not insurmountable. The growing base of consumers ready and willing to support their local producers, not to mention make better and healthier food choices for themselves and their families, helps ensure the success of cottage food operations.

Of course, as always, we at FTCLDF stand ready to support your livelihoods and we can help you get your home food business off the ground. It’s a value-added benefit we provide to our members who, luckily for us, return the favor by employing their time, expertise, and passion to create a bounty of irresistible delicacies in their own home cottages.

Your Fund at Work

Services provided by FTCLDF go beyond legal representation for members in court cases.

Educational and policy work also provide an avenue for FTCLDF to build grassroots activism to create the most favorable regulatory climate possible. In addition to advising on bill language, FTCLDF supports favorable legislation via action alerts and social media outreach.

You can protect access to real foods from small farms by inviting others to become a member or by donating today.